Update, 1 July 2012: a recording of Rendezvous With Destiny is now available on iTunes.

I have to thank Bob Carr for introducing me to the poetry of Stephen Vincent Benét. I confess I had only known of Benét as the author of the short story The Devil and Daniel Webster.

Bob and I started talking two years ago about a musical collaboration, to create a concert piece for narrator and musical ensemble for which I would compose the music and he would speak a text chosen by us.

I’m happy to say that on April 3rd, the world-premiere of Rendezvous with Destiny will take place at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. This work for narrator and chamber ensemble will be performed by the New Sydney Wind Quintet with Bob narrating. (Tickets can be purchased here.)

Rather than select a single source as the text, we decided to challenge ourselves by creating a modern cento. Originating in Classical antiquity, the Latin cento was a poem made up entirely of lines from existing poems. This may seem weird against today’s artistic values that place so much emphasis on originality, but in fact the centonist’s art was admired precisely because it allowed the poem to borrow meaning: a knowledgeable audience would grasp the whole inherited background behind a single borrowed line. The 4th century Roman poet Ausonius wrote that a cento lets “different meanings come together in a single form, and disparate things seem to be related, so that unrelated things let no light through the gaps….”

(The cheeky Ausonius himself managed to create a baudy piece about wedding night deflowering by joining up lines entirely from Virgil, no less.)

Though rarer, there were also centos of non-poetic assemblages, ie. the prose centos that Eustathius mentions. In music, the most famous example is the text of Messiah by Charles Jennens that Handel set to music in which some 80 independent passages are concatenated from biblical books to tell the Bible’s central story.

Bob and I have a mutual interest in American history. You’d have thought this would be the obvious subject for our text. But we actually started elsewhere – Greek mythology, contemporary Australian authors – in a misguided effort to avoid the most obvious of topics: Abraham Lincoln.

Bob is known as an expert on Lincoln. I, while no expert, have accumulated a lot of Lincoln lore because I just happen to be born on the same day of the year (Feb 12), and my childhood was full of needling about following the footsteps of a great leader.

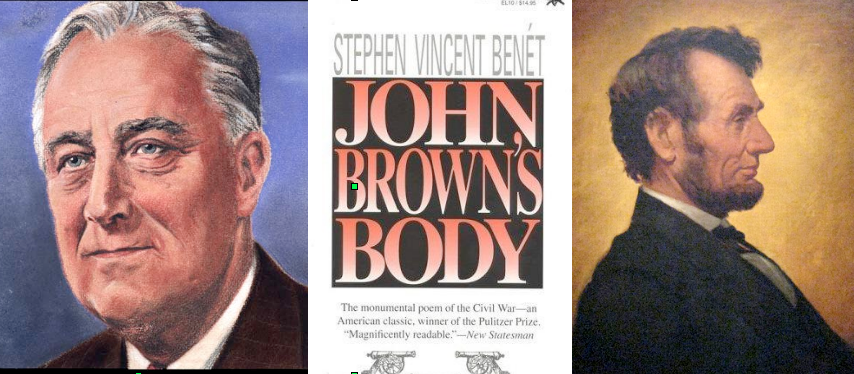

Bob is also a longtime admirer of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. When he proposed FDR, I was immediately intrigued: both Lincoln and Roosevelt were wartime presidents. I knew that juxtaposing words from the Civil War and the Second World War periods would fulfil Ausonius’ criterion of disparate things seeming related.

We felt we needed one more source to ‘glue’ our wartime presidents together. It was then that Bob suggested the poet Stephen Vincent Benét. A brilliant choice; Benét was an exact contemporary of Roosevelt’s who greatly admired this longest serving of America’s presidents. He even wrote a section of Roosevelt’s famed Four Freedoms speech.

The Civil War was a central theme in Benét’s poetry. Benét won the first of his two Pulitzer Prizes for his book-length poem John Brown’s Body, an extraordinary epic lyric chronicling the era and the man whose death in the process of protesting slavery ignited the Civil War.

And so our text begins with Roosevelt and Benét simultaneously: Benét’s tribute poem to Roosevelt, called Tuesday, November 5th, 1940 [Election Day]. In the deliberately plain, street-tone of ‘ordinary’ people, Benét gives voice to a nation grateful to a president who had seen them safely through the Great Depression, when the “merry-go-round broke down”.

Then we intermingle lines from two powerful speeches of Roosevelt’s: his address before the Democratic National Congress of June 1936 and his second inaugural address of January 1937: the former is the rousing ‘Rendezvous with Destiny’ speech; the latter contains that chilling observation, “I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad and ill-nourished.”

The simply-worded but heartfelt United Nations Prayer, written by Benét expressly for and delivered by Roosevelt on Flag Day, June 14, 1942, forms our transition to a section of poetry of Benét’s.

The next stanzas, with their gorgeous imagery and rippling meters, come from The Ballad of William Sycamore and American Names. The latter’s most famous line is its very last: “Bury my heart at Wounded Knee”; for us it forms a natural link to the brutal and vivid closing section of John Brown’s Body, where Benét declares that the whole old South buried itself when it hanged John Brown.

And finally to Lincoln. The theme of mortality brings us to the condolence letters of Abraham Lincoln. There exist at least 2 letters by Lincoln expressing his sorrow and respect to the family of soldiers killed in the war. This is an Abe Lincoln far removed from the larger-than-life persona of the Gettysburg Address or the Second Inaugural Address. They reveal instead a compassionate leader, even a friend.

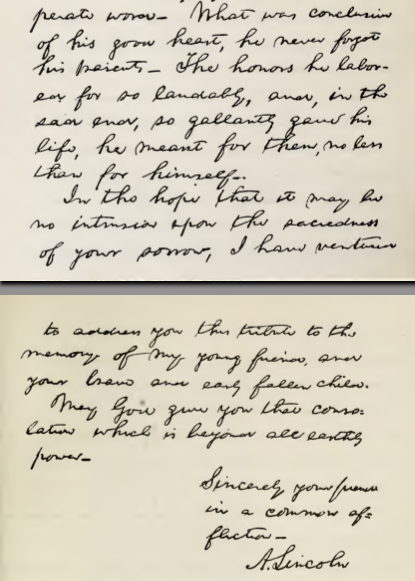

The first is the letter to the parents of Elmer Ellworth, written “in the hope that it may be no intrusion upon the sacredness of your sorrow.” The 24-year old Colonel Ellsworth was not only a close friend of Lincoln’s, but the first casualty of the Civil War. Lincoln was shattered at this loss and his emotion is absolute and plain in the letter.

The other is the famous “Bixby Letter,” a succinct, beautiful expression of consolation to a Mrs Bixby of Massachusetts who lost five sons in the war. The Bixby Letter is often cited as a model of perfection of its kind. Never mind that three of Mrs Bixby’s sons actually survived the war, that Mrs Bixby herself was a Confederate sympathiser with little regard for Lincoln, or that the letter, though issued with Lincoln’s approval, was probably penned by Lincoln’s secretary John Hay (clearly an accomplished writer in his own right).

With this wide range of texts, I felt able to adopt a commensurate range of musical styles that nonetheless cohered. Sometimes I matched music and word logically: I threw in the bustle of a brief 1930’s dance-hall passage to accompany the “creeping panic” of Benét’s Tuesday poem. To illustrate New Deal industrial stimulation, I indulge in some musical onomatopoeia alluding to locomotive music. But as for actual quotation, I did this only once and only obliquely – I borrow from James Sanderson’s Hail to the Chief not in any of the presidential texts but to create the slow, inexorable march of the John Brown poem.

For the same reason a cento text allows meaningful connections to be made across disparate sources, I sometimes use the same music for disparate texts. For instance, I used the same noble theme for the the United Nations Prayer and for the postlude following the Lincoln condolence letters, both texts being acknowledgements of the will of a higher power.

And so in the end, what have Bob and I created? Merely a way of glancing at America, merely an appreciation of its story by burrowing deeply into a handful of moments we’ve chained together.

Personally, the country where I spent so many formative years fascinates me still, a country that has the best and worst of everything. The poet Robert Pinsky observed that America has no origin story: “Americans have been suckled by no wolf, sired by no Trojan fleeing Troy; they are not descended from the sun or from dragon’s teeth sown in the earth…. The greatness of our nation, then, may consist partly in its ability to thrive, to endure, and to evolve without certain marks of peoplehood. Indeed, a major, traditional American proposition has been that our greatness consists precisely in the fact that we are making it up as we go along — that we are perpetually in the process of devising ourselves as a people.”

I’d say the longer America exists, the more its stories function like origin myths: that America invents itself in the overcoming of slavery, in the triumph over depressions, in the evolution of its morality and spirituality, in the falling in love with its own names. Pinsky ended his essay with this profound sentence: “Deciding to remember, and what to remember, is how we decide who we are.”

Here is the complete speaking text, with sources identified.

[Benét: “Tuesday, November 5th, 1942”]

We remember, F.D.R.

We remember the bitter faces of the apple-sellers

And their red cracked hands,

We remember the gray, cold wind of ‘32

When the job stopped, and the bank stopped,

And the merry-go-round broke down,

And, finally,

Everything seemed to stop.

The whole big works of America,

Bogged down with a creeping panic,

And nobody knew how to fix it, while the wise guys sold the country short,

Till one man said (and we listened)

“The one thing we have to fear is fear.”

Well, it’s quite a long while since then, and the wise guys may not remember.

But we do, F.D.R.

It’s written in our lives, in our kids, growing up with a chance,

It’s written in the faces of the old folks who don’t have to go to the poorhouse

And the tanned faces of the boys from the CCC,

It’s written in the water and the earth of the Tennessee Valley

The contour-plowing that saves the dust-stricken land,

And the lights coming on for the first time, on lonely farms.

[Roosevelt: Speech before the 1936 Democratic National Convention]

America will not forget these recent years.

We feared fear. That was why we fought fear. And today, my friends, we have won against the most dangerous of our foes. We have conquered fear.

[Roosevelt: Second Inaugural Address, Jan 1937]

Shall we pause now and turn our back upon the road that lies ahead? Shall we call this the promised land? Or, shall we continue on our way? For “each age is a dream that is dying, or one that is coming to birth.”

Many voices are heard as we face a great decision. Comfort says, “Tarry a while.” Opportunism says, “This is a good spot.” Timidity asks, “How difficult is the road ahead?”

In this nation I see tens of millions of its citizens who at this very moment are denied the greater part of what the very lowest standards of today call the necessities of life.

I see millions of families trying to live on incomes so meager that the pall of family disaster hangs over them day by day.

I see millions whose daily lives in city and on farm continue under conditions labeled indecent by a so-called polite society half a century ago.

I see millions denied education, recreation, and the opportunity to better their lot and the lot of their children.

I see millions lacking the means to buy the products of farm and factory and by their poverty denying work and productiveness to many other millions.

I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.

It is not in despair that I paint you that picture. I paint it for you in hope—because the Nation, seeing and understanding the injustice in it, proposes to paint it out.

[Roosevelt: Speech before the 1936 Democratic National Convention]

There is a mysterious cycle in human events. To some generations much is given. Of other generations much is expected. This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.

[Benét: Flag-Day Prayer, June 14, 1942, delivered by Roosevelt]

Our earth is but a small star in the great universe. Yet of it we can make, if we choose, a planet unvexed by war, untroubled by hunger or fear, undivided by senseless distinctions of race, color or theory.

We are all of us children of earth. If our brothers are oppressed, then we are oppressed. If they hunger we hunger. If their freedom is taken away our freedom is not secure. Grant us a common faith that man shall know bread and peace – that he shall know justice and righteousness, freedom and security, an equal chance to do his best, not only in our own lands, but throughout the world. And in that faith let us march toward the clean world our hands can make.

[Benét: American Names]

I have fallen in love with American names,

The sharp names that never get fat,

The snakeskin-titles of mining-claims,

The plumed war-bonnet of Medicine Hat,

Tucson and Deadwood and Lost Mule Flat.

[Benét: The Ballad of William Sycamore]

Go play with the towns you have built of blocks,

The towns where you would have bound me!

I sleep in my earth like a tired fox,

And my buffalo have found me.

I died in my boots like a pioneer

With the whole wide sky above me.

[Benét: American Names]

I shall not rest quiet in Montparnasse.

I shall not lie easy at Winchelsea.

You may bury my body in Sussex grass,

You may bury my tongue at Champmedy.

I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass.

Bury my heart at Wounded Knee.

[Benét: John Brown’s Body]

John Brown is dead, he will not come again,

A stray ghost-walker with a ghostly gun.

Let the strong metal rust

In the enclosing dust

And the consuming coal

That was the furious soul

Grow colder than the stones

While the white roots of grass and little weeds

Suck the last hollow wildfire from the singing bones.

Bury the South together with this man,

Bury the bygone South.

Bury the minstrel with the honey-mouth,

Bury the broadsword virtues of the clan,

Bury the unmachined, the planters’ pride,

The courtesy and the bitter arrogance,

The pistol-hearted horsemen who could ride

Like jolly centaurs under the hot stars.

Bury the whip, bury the branding-bars,

Bury the unjust thing

That some tamed into mercy, being wise,

But could not starve the tiger from its eyes

Or make it feed where beasts of mercy feed.

Bury the fiddle-music and the dance,

The sick magnolias of the false romance

And all the chivalry that went to seed

Before its ripening.

And with these things, bury the purple dream

Of the America we have not been,

Bury this destiny unmanifest,

This system broken underneath the test,

Beside John Brown and though he knows his enemy is there,

He is too full of sleep at last to care.

[Abraham Lincoln: letter to the parents of Elmer E. Ellsworth]

My dear Sir and Madam,

In the untimely loss of your noble son, our affliction here, is scarcely less than your own– So much of promised usefulness to one’s country, and of bright hopes for one’s self and friends, have rarely been so suddenly dashed, as in his fall. In size, in years, and in youthful appearance, a boy only, his power to command men, was surpassingly great– This power, combined with a fine intellect, an indomitable energy, and a taste altogether military, constituted in him, as seemed to me, the best natural talent, in that department, I ever knew. And yet he was singularly modest and deferential in social intercourse– I never heard him utter a profane, or an intemperate word– What was conclusive of his good heart, he never forgot his parents– The honors he labored for so laudably, and, in the sad end, so gallantly gave his life, he meant for them, no less than for himself–

In the hope that it may be no intrusion upon the sacredness of your sorrow, I have ventured to address you this tribute to the memory of my young friend, and your brave and early fallen child.

May God give you that consolation which is beyond all earthly power–

Sincerely your friend

in a common affliction–

A. Lincoln

[Abraham Lincoln / John Hay: Letter to Mrs Bixby of Massachusetts]

Washington, Nov. 21, 1864.

Dear Madam,–

I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts, that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle.

I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the Republic they died to save.

I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours, to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of Freedom.

Yours, very sincerely and respectfully,

A. Lincoln